Nelson Alburquenque talks to Chelsea Bighorn, Joseph Maldonado, and LeOreal Wall

On April 21st, as part of the Art in Conversation side-project, I was afforded the opportunity of engaging in fluid conversation with three senior studio arts students to talk about craft and life in the pandemic. The three students I talked with were Chelsea Bighorn, Joseph Maldonado, and LeOreal Wall. The following is a recap from that day.

___

C h e l s e a B i g h o r n

The day of conversations began with me chatting with Chelsea Bighorn (Assiniboine and Sioux). Immediately, Bighorn’s art stuck out from the peers I was assigned, mostly notably because of its ordered focus in geometric shapes and patterns. Where the other artists’ works I was assigned dealt with characters and played off of space (or the lack thereof), Bighorn’s work dealt in refined angles, symmetry and asymmetry. Immediately, Bighorn’s work reminded me of Andrea Otero’s geometry course, The Art of Mathematics (a course I highly recommend), where similar shapes to Bighorn’s shapes and patterns are examined. When I asked about where the origin of her work came from, she answered to the point. “I started out looking at stain glass windows and (it) just evolved from there.” Her fascination with the stain glass architecture, most prominently associated by major audiences with the churches, is reflective in her own approach to the form, particularly in her piece “Untitled 2”. At first glance, “Untitled 2” looks as though it were a photo taken from within a church in on an early winter’s evening. There is a sleepiness to it and one may imagine a warm fire nearby, however it is not a photo but a mixed media piece, carefully crafted so well that it is mistaken for a real-life photograph. On the process Bighorn recalled, “I start out with the general shape that I know I want to work off of. From there I try to do everything on the paper first hand, but that gets so messy, so I’ll move to digitally. Triangles and diamonds. From there, I’ll lay it on the paper and sit from what feels like days and weeks on end. I’ll hand cut it all out and paint it black.” As our conversation concluded, we talked about life in the pandemic. Bighorn stressed that her work is best observed in person, as opposed just through virtual means. Where in digital form, her pieces are presented in one angle, in person a viewer is likely to interpret the shapes in different ways, noticing how they interact with the lighting and perspective. We ended our conversation looking forward to the day when the wounds of the pandemic may finally be healed.

J o s e p h M a l d o n a d o

Next I met with Joseph Maldonado, who, full disclosure, is a good friend of mine at the Institute of American Indian Arts. Curiously, despite being friends, we had barely skimmed the surface in conversation regarding our respective arts. I entered the conversation eager to hear about Maldonado’s processes and the roots of his series’ creation.

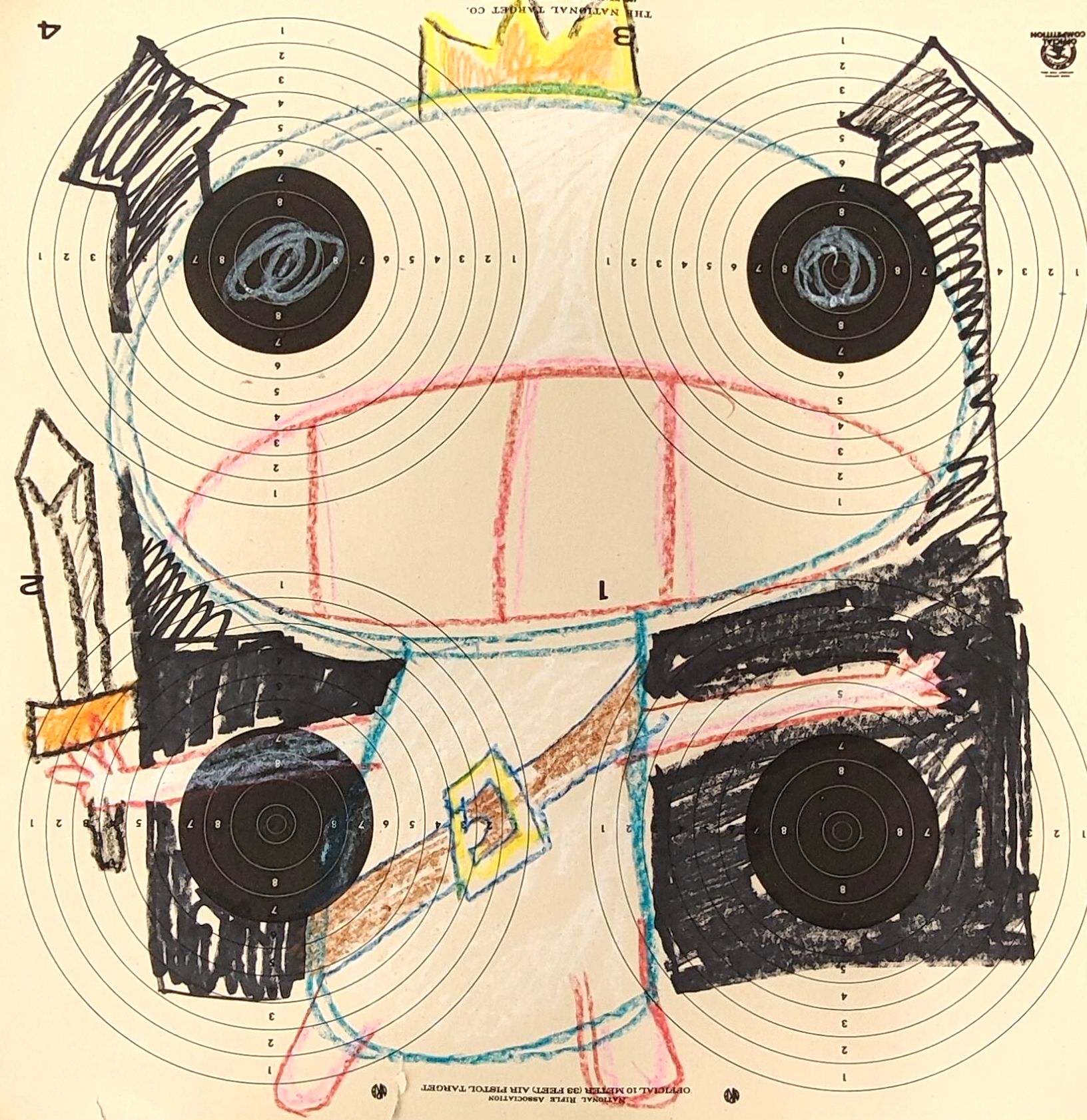

What immediately became notable to me about the series Maldonado shared was the embattled nature of his cartoony characters, many of whom appear like warriors bearing gritty expressions of survivance. In one, a warrior dawns boxing gloves. In another, a warrior carries a sword. Of the six pieces, no warrior appears twice. Each is unique, yet all the warriors share a resilient yet battered expression, living in a canvas world (divided in four sections marked by four targets) that is violent and unfriendly. On first glance, I had interpreted the warrior series to be almost a like a collective self-portrait of Maldonado himself navigating the terrain as living as an artist with an outspoken heart, critiquing the views held by modern Western society. Maldonado elaborated that warrior series (and his other recent works) was more inspired by going stir-crazy in the pandemic, a reflection on being in ‘lockdown’, feeling put in a box. Maldonado’s explanation was an ’ah-ha!’ moment in the conversation. Immediately, my eyes turned to “Zoo Animal”. Though “Zoo Animal” was not part of the warrior series, this piece seemed to summarize the spirit of Maldonado’s words explaining the impact COVID-19 had on his recent works. In the piece, a cat is locked behind bars with its eyes nearly popping out and its hair standing on end, implying a state of disarray. Above the cat the words “feeling like a caged zoo animal” can clearly be read. In this piece, I could see Maldonado as the cat, expressing the adverse impact of Zoom classes and social distancing has had on his mental state as an artist and free-spirit.

Of the many works of Maldonado we went on to discuss, “Last Dinosaur” became a fixture. Here, we took a break from talking about the pandemic and began discussing archeology and the impact of the discipline has had on Native peoples around the world. In “Last Dinosaur”, Maldonado creates a child-like doodle of a green tyrannosaurs with body designs. The dinosaur is surrounded by buildings which are equally as doodly (yes, I have made that a word) as the dinosaur. Unlike “Zoo Animal” and some of Maldonado’s other works, there is no text to accompany the piece, so a viewer is left to meditate on what is given. When asked about the origin of the piece, Maldonado revealed that one of his first academic interests was the study of archeology, where he obtained a degree. He went on to talk about his conflicted feelings about the academic discipline, especially when it came to Native peoples; how on the one hand it could be used to learn about certain histories, genetics, and customs – but on the other hand, it could be (and is often) used to make a spectacle out of Native peoples, turning them into a kind of academic fetish that is almost denigrating and circus-like.

On this subject, I recounted a 2016 trip I took to Peru with Santa Monica College. It was one of the greatest trips of my life, in part because it brought me closer to the land of my blood ancestors of “South America”. However, towards the end of the trip – after visiting Cuzco and Machu Picchu – our group stayed a few nights in the colonial town of Arequipa. There, on a day off, I went to visit the Museo Santuarios Andinos, where I came face-to-face with one of the “Ice Maiden” children, a group of preserved Incan children who were taken from their resting place at the top of Mt. Ampato in 1995, studied, and kept for display as a tourist attraction. I recalled the eeriness I had felt standing just feet away from one of the girls (“Sarita”) who had lived over 500 years ago. On the one hand, I felt a serious honor to be in the same room as the sacred child. On the other, I felt sick, sick because it was never the intention of the child’s people for her to be kept in a museum; she belonged on the mountain. I explained to Maldonado that because the offered child had been taken and studied, many things were learned about her. At that time, the contents of her stomach were still preserved (thanks to the unbearable cold of the mountain), and that gave further insight into the Incan diet, particularly in Cuzco. Yet, at the end of the day, one could not ignore the blatant fact that Western fascination had stolen the sacred children from their burial site. In looking at “Last Dinosaur” and talking about the children of Mt. Ampato, Maldonado and I both came to a shared sentiment: where the children (and Native items in general) ultimately belong is with their people.

L e O r e a l W a l l

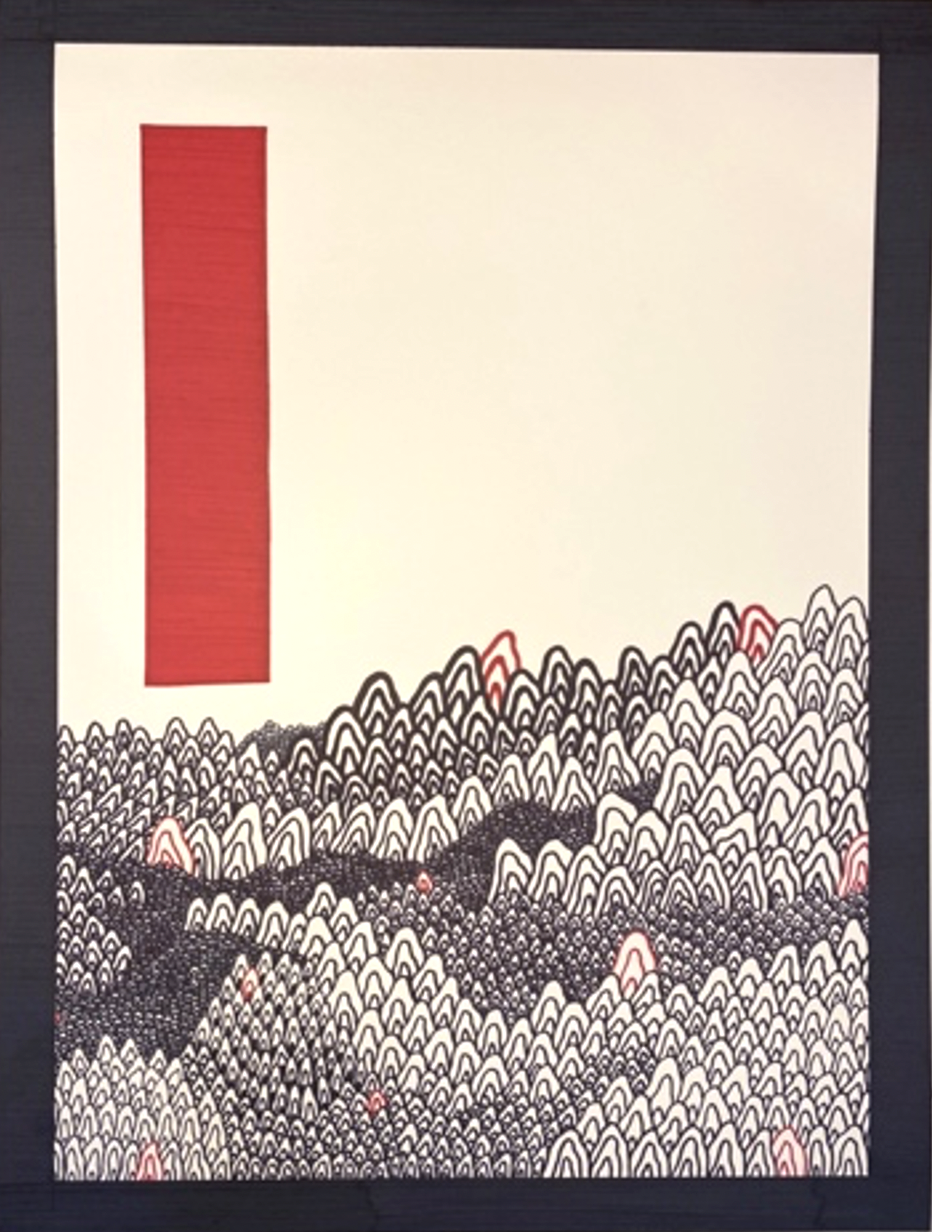

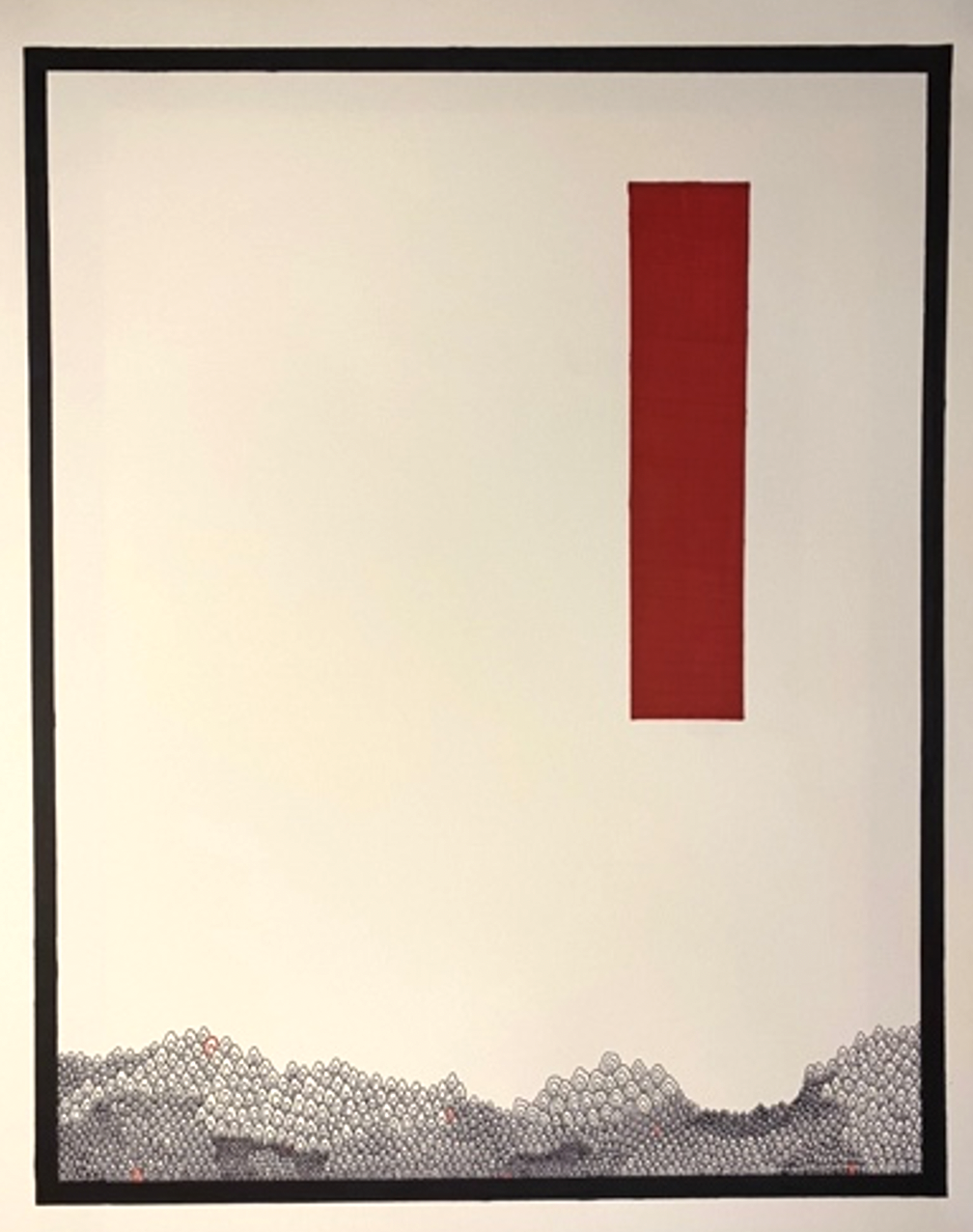

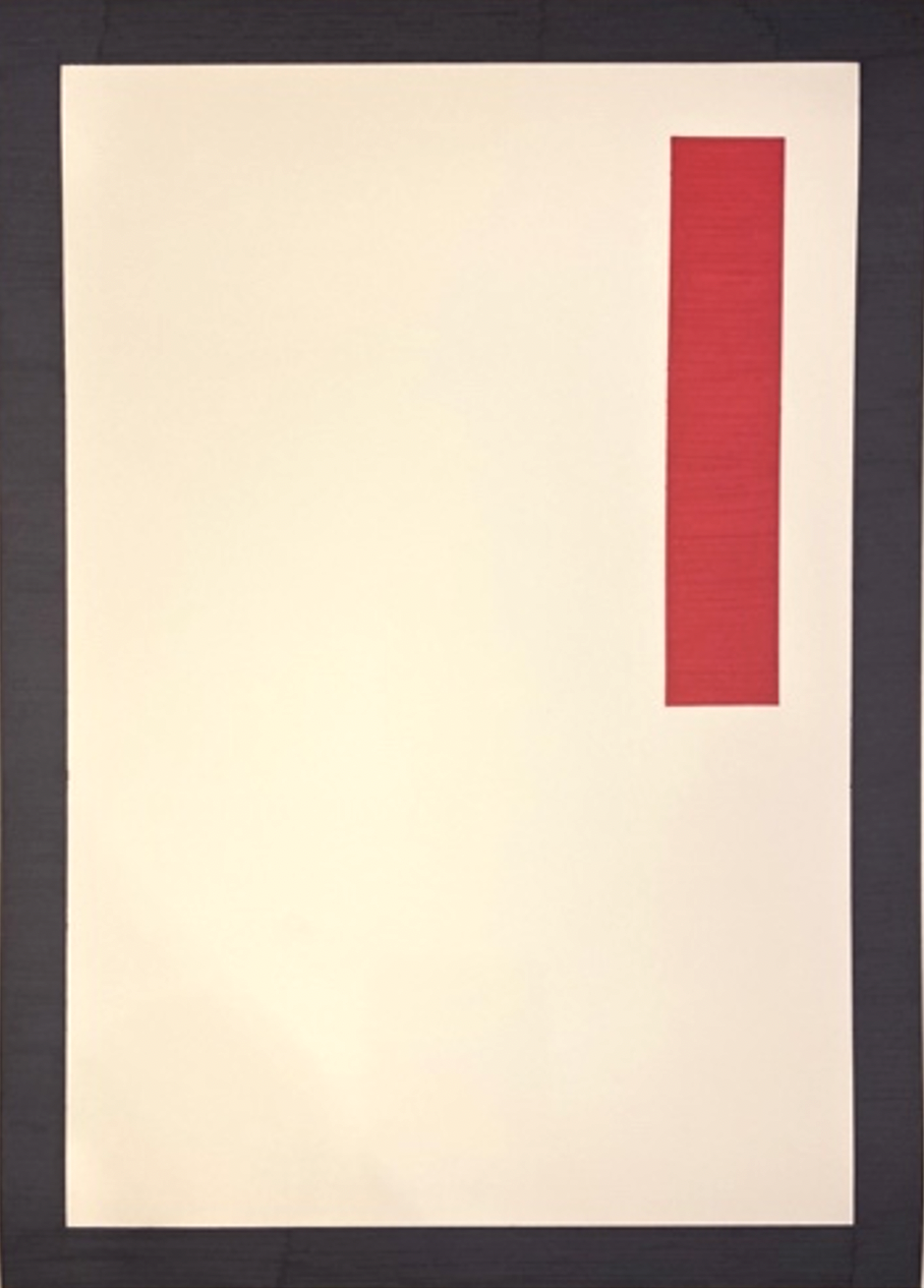

Wrapping up the day’s conversations, I talked with senior artist, LeOreal Wall (Mountain Ute, Northern Ute), about her series, “Anxiety of the Ignorance”. Playing with empty and crowding space, Wall’s pieces reflect the fears of the world becoming consumed by the pandemic. For Wall, the pandemic was (and still is) personal. In the midst of our conversation, Wall recounted how her current senior project had been the result of the studios first closing down: “Last semester, I had a completely different senior project. I was going with jewelry because that was my emphasis. I was going to do castings of shackles, with the idea (of Indigenous peoples) being contained.” Due to the pandemic, Wall found herself at a crossroads, unable to finish her project, due to social distancing precautions and a diminished access to studio resources as well as her own concerns about the virus. She, then, pivoted and created her current senior inked-based project. Explaining her process, Wall elaborated, “The way I wanted my pieces to be looked at was in person. I wanted the viewer to go see this pattern, this wave, from afar, but when you get close to it you see the different humanoid shapes, the people, built on top of each other. I wanted people to go up and look at it and be face-to-face with this and look at the piece like how I was with my face to the paper making these tiny shapes.” Further explaining, the work, Wall continued, “I felt like [the series] was my coping mechanism throughout 2020 of dealing with the anxiety and the world at large – getting overwhelmed with that. I felt like I needed to do something to focus my mind.” The border that surrounds each piece, Wall explained, was a metaphor for being trapped in lockdown. Looking at them again, it became clear to me that the space and the designs inside them were also metaphors: metaphors understanding and navigating a new path in the pandemic. As we continued to talk, Wall went on to explain that the series was also as much a meditation on being Indigenous and a person of color as it was a time stamp inspired by the pandemic. “The concept of where we (Indigenous) stand was really something I was thinking about, that concept of being Indigenous or a person of color in a group of non-Indigenous voice and how our (Indigenous) voice is shown not to matter and is quieted. [I ask] how do we stand out from them? How do we pursue that identity and make it known?”

Ultimately, what became clear to me from the Art in Conversation project was the massive impact the 2020-2021 pandemic lifestyle has had on Institute of American Indian Arts students. The pandemic has left many students feeling isolated from their peers and going stir-crazy, even within their own community and own home. The deprivation of physical humun-to-humun interaction has been, in many ways, detrimental to each artist’s mental health, their hopes, and their dreams.

However, there was another takeaway – a silver lining.

What was just as clear from talking to Chelsea Bighorn, Joseph Maldonado, and LeOreal Wall was the takeaway that art for our student body is so much more than a passion or degree plan. Art is our medicine. At the end of the day, when we lose everything else, we turn to our art. For Bighorn, that medicine is the medicine of shapes and angles. For Maldonado, that medicine is of character expression. For LeOreal, that medicine is the medicine of space and making new starts, finding new space and growing a garden of art within it. For these three senior studio artists, art is medicine. Art is resilience.